This is the second of a two-part series on the nomination of Garland Merrick to the Supreme Court. You can read Part 1 here. As with every thing else in this upside-down year, Democrats are arguing precedent, while Republicans are arguing for “situation ethics.” This page will cover the GOP argument against confirming the President’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland.

Let’s face it. The GOP argument is not really about “lame duck” appointments. Mitch McConnell’s refusal to even talk to President Obama’s nominee has been compared to his comment from 2010:

“The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

But people seldom cite his very next line in the interview:

“If President Obama does a Clintonian backflip, if he’s willing to meet us halfway on some of the biggest issues, it’s not inappropriate for us to do business with him.”

That sounds just as cooperative as the second part of Joe Biden’s quote in 1992 in our last page. So what is the current argument really about? It’s about the future of the Supreme Court.

Biden noted that the combination of FDR and Truman moved the court to a very liberal view, and the combination of Reagan and Bush41 moved the court to a very conservative view. The real message Biden was giving was not about election-year nominations. It was about the danger of having presidents move the court too far one way or the other.

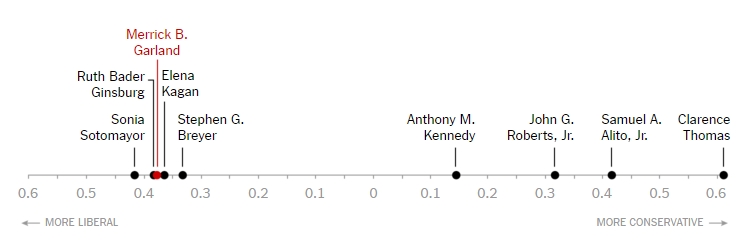

So where are we now? The New York Times gives us a graphic, showing where the Justices sit on the ideological scale:

As you can see, Merrick Garland is not really a “centrist,” except that he’s “in the middle” of the left wing. He is considered as liberal as Samuel Alito is conservative.

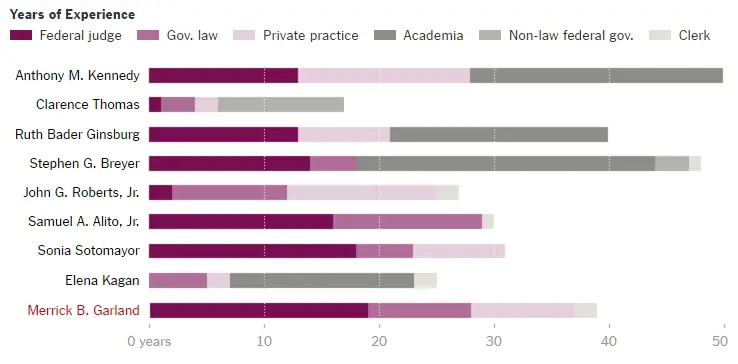

Also, Merrick certainly has enough experience. This graphic shows that his experience is not as much as Kennedy’s, but more than twice as much as Clarence Thomas.

This is the real Republican concern—flipping the court against them.

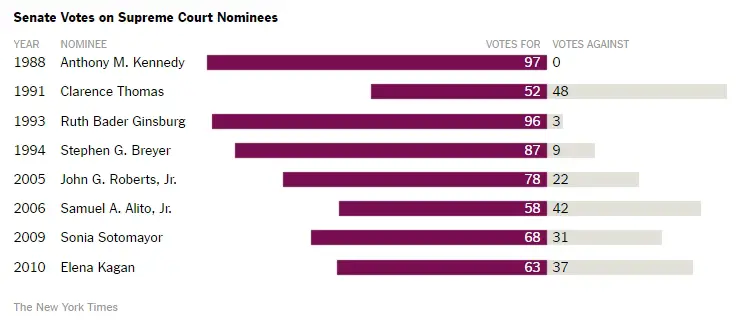

But there’s another concern. That is the increasing partisanship. This graphic shows that all the current Supreme Court nominees (except for Clarence Thomas) have received fewer and fewer supporting Senate votes as the years have gone along—from 97 votes for Kennedy to only 63 for Kagan.

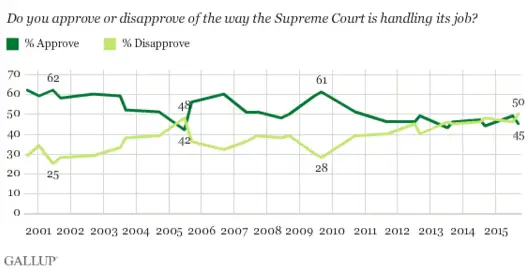

So year after year, the Supreme Court has become more and more politicized. And that has impacted the public’s respect for the court.

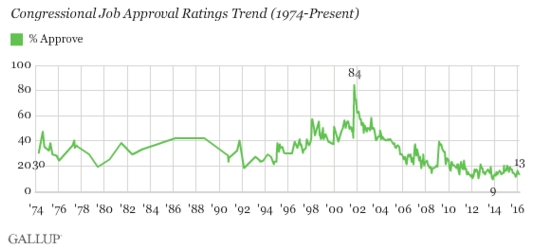

This chart shows that in 2001, 62% of the people approved of the Supreme Court, with only 25% disapproved. At the end of last year, 50% of the people disapproved of the Supreme Court, with only 45% approving. [Meanwhile, Congress has an approval of only 13%, so they can’t point a finger at the other branch.]

All institutions seem to be losing respect.

While Senator Orrin Hatch is on record as praising Judge Merrick’s qualifications and capability back in 1997, but he agreed with Biden in 1992—that an election year nomination can be divisive:

“members of the Supreme Court are aware that a confirmation battle in an election year would be so divisive that anyone contemplating retirement would probably delay doing so until after the election.”

Meanwhile, in the same article, and also I 1992, Minority Whip Sen. Alan Simpson disagreed.

“It’s not for the chairman of the judiciary committee to decide who the president of the United States submits as a nominee to the United States Supreme Court.”

So, as you can see, the Democrats are saying, “we should get our nominee, because it’s always been that way.” Meanwhile, Republicans are saying, “Yeah, but look at where that has taken us.”

There is no question that the country is more divided—and more hostile—that it has ever been, at least since 1968. The presidential race is dividing us further. The problem is that Republicans are not offering a solution to that problem. Instead of overcoming needless partisanship, they are being partisan in blocking the Democratic nominee, hoping they’ll get a Republican nominee next year. Same old, same old.

I would like to take a step out of our normal role of repeating what is being said elsewhere. I would like to recommend a partial solution to our problem.

As quoted above, Alan Simpson says it’s not the senate judiciary committee’s job to pick a Supreme Court nominee. But my question is, why not?

The Constitution says that the President will name Supreme Court Justices “with the advice and consent” of the Senate. Why don’t we just expand the meaning of “advice”?

Imagine if the Senate Judiciary Committee drew up a list of recommended Supreme Court nominees. Both sides would have veto power, so only true centrists would be recommended to the President. Acting on that “advice,” the President would make his (or her) nomination from that list.

That would not totally preclude creative minds. Over the years, Republicans have nominated moderate to liberal justices, and Democrats have nominated moderate to conservative justices. I believe a system like this would help to reduce our divisions.

And therefore, I would like to suggest that the Republicans are right—in this case. The Judiciary Committee should consider Merrick Garland—along with a list of their own. Then, they should recommend names of judges both sides can agree on.